Imagine that you are an anaerobe. You are an organism that does not require oxygen in order to live. In fact, you despise the stuff--one whiff of fresh air can transform your well-organized membranes into a sloppy pile of broken fatty acids. Perhaps you are a fashionable Clostridium precursor to Botox, or you are instead an avant-garde Archean methanogen from Nuvvuagittuq. You're not LUCA, but you are one of her great-grandchildren; you are an inheritor of her Earth. What does your Earth look like?

Stromatolithes. CC Eeckhout, CC 3.0, via Wikimedia. Some parts of the world still look like this; this photo is from Australia circa 2008.

It looks like this, mostly. A lot of wet blobs beneath a hot atmosphere thick with methane, and upon a dense world, where stone is subducted into stone beneath pluming fields of bacterial mats, here seen fossilized into one wavy chunk of rock. The world is covered in rocks like these.

Fossilized stromatolite in Strelley Pool chert, about 3.4 billion years old, from Pilbara Craton, Western Australia. Didier Descouens, CC 4.0, via Wikimedia. A bacterial metropolis, though most things are.

Before this was a rock, it was a stromatolith, a city made from contentious layers of mineral deposits, mucus, and goopy bacteria. You, the anaerobe, are beginning to hate living in this city, and you blame this fraught relationship upon a new neighbor. Your new neighbor is an aerobe. Your new neighbor spews a constant litter of toxic garbage. Your new neighbor has produced a new, unregulated, and unsettling organ: the mechanism of photosynthesis.

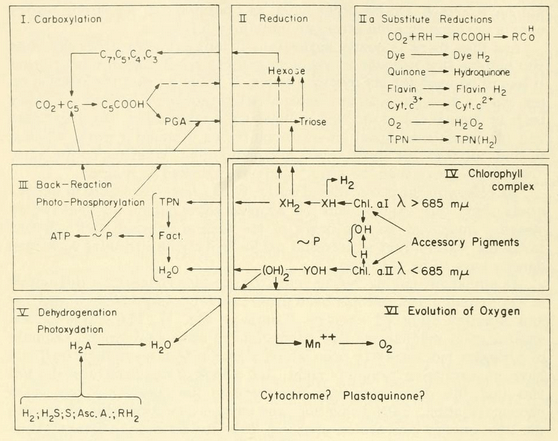

The Charles F. Kettering Research Laboratory. 'Bacterial Photosynthesis.' edited by Howard Gest, 1963, pp. 8. via Archive.org. Long live the new flesh?

Now, you're a forward-thinking citizen of the Paleoproterozoic city; the sun is a fine energy source, and anoxic photosynthesis via retinal, popular among groovy purple bacteria, is a traditional method of capturing the light. However, a niche was left open, and nature abhors a vacuum. While retinal-favoring purple organisms hogged most of the absorb-able light spectrum, the leftover wavelengths that could be captured by green chlorophyll were there for the taking. It's not the ingenious chlorophyll-utilizing cyanobacteria's fault that this then led to so many unfortunate side effects, such as causing a mass extinction event that reduced biosphere productivity by 80% and kicking off the three-hundred-million cold years of the Huronian glaciation by chemically transforming the methane-and-carbon-dioxide-based greenhouse atmosphere into a depleted icehouse. (Not only does photosynthesis release highly toxic oxygen as waste, but it also chews up the insulating blanket of atmospheric carbon dioxide in order to do so.)

Cyanobacteria (248 07) Mixture; native preparation; green filter. Dr. Josef Reischig, CC 3.0, via Wikimedia. Portrait of a killer.

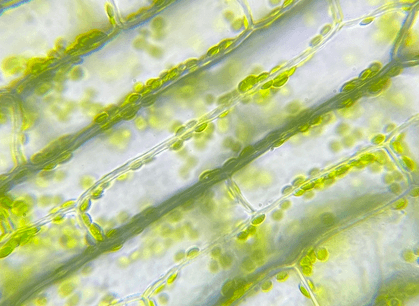

However, this was only unfortunate for you, the anaerobe, who then either died from too much fresh air or was quietly relegated to the cozily suffocative basement layer of the stromatolith. In your absence, the aerobes enjoyed the newly unlocked richness of resources for a very long time. You, the you who is reading this article, are a distant product of this glut. You, eukaryote, may be the product of bacterial invagination, of mutualistic invasion, of one living body becoming the organ of another. It is entirely possible that your famous powerhouse of the cell, the mitochondria, began as an itinerant aerobic bacteria. Eventually, that proto-mitochondrial bacteria found that sitting around inside a larger cell was way nicer than roughing it alone, and the resulting endosymbiosis led to the development of aerobically respiring animals and fungi. Plants, too, may be the result of this arrangement. In addition to mitochondria, chlorophyll-carrying cyanobacteria could have been integrated as chloroplasts.

Elodea cells under microscope. Cropped. User ~delta, CC 4.0, via Wikimedia. All the little green blobs are chloroplasts. Imagine if a guy broke into your house and started making little treats for you and so you let him stay there for the next billion years

Nowadays, photosynthesizers spew out oxygen as they turn sunlight energy into sugar, and aerobic respirators suck up oxygen as they turn sugar back into energy. Aerobic wastes, such as carbon dioxide and shit, perpetuate the cycle further by then fertilizing photosynthesizers. An ancestor anaerobe, if it had the mind to do so, could witness a vision of this alien future where the dominant lifeforms are coprophagically passing their toxins around in a big circle and go, wow, gross, but thankfully, prokaryotes are not the type to pass judgement. They are primarily concerned with growing where they can. They grow where they can until they kill their host organism, until they run out of resources, until they suffocate on their own Malthusian mass. They grow until they can't anymore. Then, they die.

Toxic algae bloom in Lake Erie. NASA Earth Observatory. Public Domain, via Wikimedia. Cyanobacteria still thrive today; those diluting swirls of green are massive colonies of the stuff.

Cyanobacteria remains a contentious neighbor. It swells in seasonal blooms, but it can also grow in response to ecologically destabilizing disasters, man-made or otherwise--anything that creates a local excess of tasty phosphorus and nitrogen nutrients. These blue-green tides produce toxins that can harm wildlife, including humans. (Red tides can be harmful, too, but those are caused by the eukaryotic Karenia brevis.) Physical exposure to bloom-clogged water can cause diarrheal illness, tissue irritation, and allergic reactions; one tragic case in 1996 saw fifty-two dialysis patients dead when cyanotoxin-contaminated water was used for their treatment.

However, the bloom begets damage beyond just toxicity; the cyanobacterial overabundance can actually lead to dangerously low levels of oxygen. As the bloom thrives, the thick layer of green scum on the surface blocks sunlight and kills underwater plants. Then, when the dead bacteria in the crowd begin to decompose, they are eaten by other bacteria, and that digesting process sucks up all the available oxygen, creating hypoxic ‘dead zones' that reduce aquatic oxygen from a healthy 8 parts per million to a mere 2 ppm. (Anything less than 6 ppm is stressful for most fish, and less than 3 will kill them.) One notable bloom dead zone, the seasonal spread of marine suffocation in the Gulf of Mexico, covers 6,500 square miles.

But the cyanobacteria cannot be wholly maligned; we should not try to scrub them out of the seas entirely. Oceanic cyanobacteria produce up to 20% of the world's oxygen. And when not prohibitively anoxic and toxic, periodic algal blooms provide food for many marine ecosystems. They are simply a case of too much of a good thing: too much oxygen, too much richness, too much of everything until the abundance collapses into a dead zone black hole -- and as bloom size and frequency increase as the Earth warms to incubate them, we may have to contend with this overbearing neighbor more and more, mostly because we keep feeding them.

Polluted river. Public domain, via Rawpixel. Tasty treat.

So, what comes from the oxygen revolution of the Paleoproterozoic? Mass death, then proliferating adaptation, fungi, plants, animals, us. What comes from the hot, acidic, microplastic-enriched oceans of the human Holocene?

Something unimaginable.

David Cronenberg, 'Crimes of the Future,' 2022. (3:43). Tasty treat.

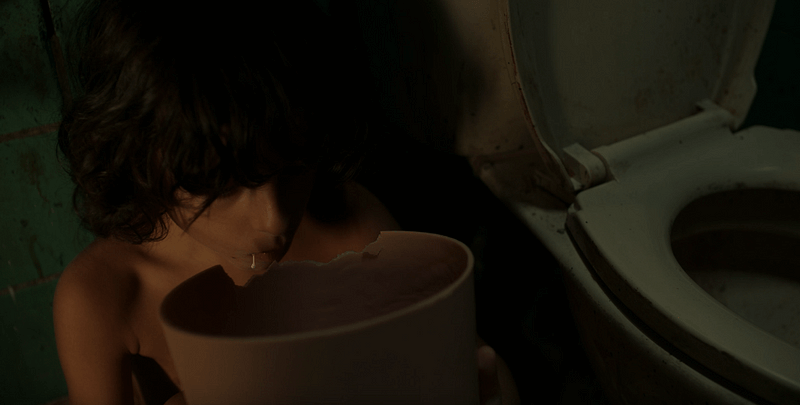

Crimes of the Future opens with a child suffocated by his mother.

Before his murder, he is scolded for trying to eat plastic waste on the beach, and then he happily munches the rim of a grimy bathroom trash can. He contains new organs. He exhibits a novel metabolism. He is something post-human, or at least he does not fit the confines of human as defined by this world's bureaucracy, or as defined by his the narrow aim of mother's repulsed gaze. But then he is murdered, and the movie continues; we follow Saul Tenser's escapades in bespoke womb-beds, breakfast chairs, and biomechanical performance art. But in the audio, in the air, there is the persistent buzzing of flies.

Crimes of the Future is a movie about sex, about not having sex, about post-sex surgery, artistic reproduction, political organs, discomfort, adaptation, evolution, and et cetera. It is probably not a parable of James Lovelock's Gaia hypothesis, where the Earth, as an aggregate organism, trends towards self-regulation. In the Gaian view, life begets life, and it perpetuates its own ideal conditions: water goes through a cycle, oxygen goes through a cycle, carbonate and sulfur and nitrogen all go through robust and elastically responsive cycles.

Crimes is probably also not a dramatization of Peter Ward's direct response to Lovelock, The Medea Hypothesis, where the evolution of life instead 'triggered a series of disasters that are inimical to life.' Ward traces the repeating cycle of extinction: Gaia blooms, suffocates, blooms, suffocates, blooms again, suffocates again. Earth murders her children, or at the very least, she leaves them to choke on their own waste.

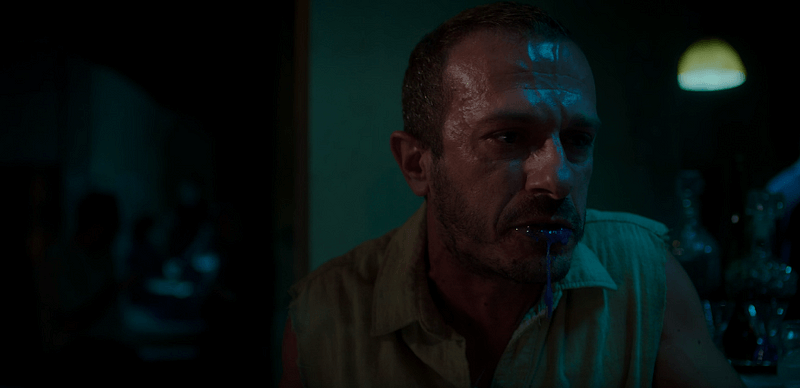

David Cronenberg, 'Crimes of the Future,' 2022. (30:19). Tasty treat?

Tyler Volk's wasteworld hypothesis may be closest to the ecological ethos of Crimes: one microbe's trash is another microbe's treasure, and one man's garbage ingot is another man's candy bar. 'We've got to start feeding on our own industrial waste,' Dotrice proclaims as he displays his surgical scars to Tenser, revealing his modified digestive system. 'It's our destiny.'

Under the evolutionary pressures of the wasteworld, some new kind of animal will surely arise to take care of the human-produced garbage cycle; actually recycling all of the bottles that we put in our recycle bins is way too cost-prohibitive, after all. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which covers 620,000 square miles, twice the size of Texas let alone its local Gulf dead zone, could plausibly be devoured by the engineered genetic chimera of plastic-eating Ideonella sakaiensis and saltwater-sturdy Vibrio natriegens, or by the convergent arrival of some other new-niche-filling plastivore microbe--but would a superbloom the size of two Texii be, yet again, too much of a good thing?

David Cronenberg, 'Crimes of the Future,' 2022. (55:20). Invagination?

In the world of Crimes, there is no more pain, no more infection; 'nobody washes their hands anymore,' but desktop surgery is still 'repulsive.' Surgery is the new sex, but people are still having kids. The New Vice unit hunts down instances of evolutionary derangement; Saul still plucks out his own idiopathic instances of accelerated evolution syndrome. He invents new organelles. The rubric of humanity falls from focus. The boundary of the body blurs. These bordered definitions are still maintained through violence, but the sea change has already occurred. The old germs have disappeared. Humans are the new prokaryotes. Or, humans are playing a part in a script that was once exclusive to microbes and asteroids: they are driving a brand new extinction. This collapsing of biological domains, however, does highlight the key difference between you and an anaerobe: autopsia.

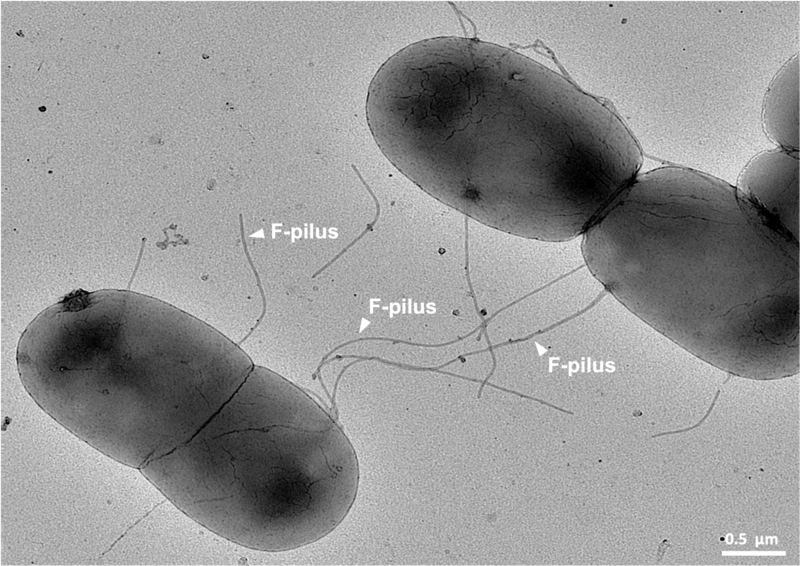

Bacterial conjugation. Jonasz Patkowski, CC 4.0, via Wikimedia. I don't think I can show anything more risqué than zipperlingus in a Medium article so have this photo of bacterial sex

You, a human, can see yourself, dissect yourself: you can make a conscious choice. Can a bacteria make a choice? Perhaps: between taxis and kinesis, in response to a measured quorum, or when choosing a partner for lateral gene transfer, the closest thing bacteria have to sexual reproduction. But the complex mechanism of conscious choice is something that a human is quite good at and a Clostridium is not. Bacterial evolution is a gambling game. In Crimes, human evolution is by our own design--but we do have to be brave enough to wield the scalpel.

Here, the world of humanity is faced with a choice: allow Brecken's autopsy and see the beautiful new world inside, or hide that impossible vista away through subtle bureaucratic subterfuge and two drills to the head. New Vice is too frightened of categorical instability, of these unregulated changes cascading out of control, and perhaps of extinction in the face of a more ecologically fit plastic-eater, and so the bureau makes a choice. And when the choice is made, Brecken, the little Lamarckian miracle of diagonal gene transfer, is suffocated in every way; humanity's main limiting factor is itself.

But Tenser, the quadruple-agent and true believer, may yet be a lateral recipient himself. He has vestigial dreams of an extinct humanity's physical pain as his body prepares to birth humanity anew. He takes a nibble of the garbage-bar, and his agony transforms into ecstasy. The novel organs of his body, once allowed to bloom, have produced the same beautiful and unknown future that Dotrice's aimed evolution had hoped for.

David Cronenberg, 'Crimes of the Future,' 2022. (1:40:55). Happy Earth day!