If you are reading this article on the internet, then there is a good chance that you are a user of electricity.

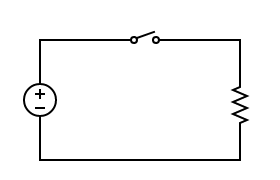

A simple diagram of a circuit with a DC source, a toggle switch, and a load.

Electricity can be imagined as the movement of electrons. When electricity is provided by a power supply, such as a battery or a plug in your wall, then the electrons are able to ‘flow’ through a conductive element, such as a wire. They are not able to flow through a non-conductive element, such as the safe-to-touch rubber sheathing of a power cord, or the air-filled gap between an unplugged device and an outlet after you have tripped on that power cord and yanked the thing out.

In the diagram above, the two circles with the tilted line between them represent a toggle switch. This is a switch that can be left open, thus breaking the circuit, or closed, connecting the circuit and allowing electricity to flow.

How is electricity put to work? The zig-zag line on the right represents a resistor. A resistor introduces resistance to a circuit; resistance is the electrical analogue to physical friction. If you rub your hands together, the friction generates heat, and you feel your palms grow warmer; if you pass electricity through a resistor, the electricity has a harder time moving as the electrons careen around the resistor’s atoms, and heat escapes. If the resistor happens to be a tungsten wire, both heat and light escape, and you get an incandescent light.

Lightbulb. Josch13, CC 0, via Wikimedia. And it was good.

Much usefulness is introduced by resistance, or by friction. This includes mental friction. Take the oft-quoted factoid that taking notes by hand boosts students’ recall when compared against simply tapping them into a laptop. The concept of “cognitive disfluency” supposes that encountering a form of mental resistance produces light; that having to actually work on something engenders a deeper understanding of it. This seems like a given. It also seems like another pop-psych self-help buzzphrase. But I do think that the utility of it is true at some median. Maximum mental resistance has us chipping essays into great stone monoliths, considering each elemental bit of data in a neurotic asymptote of atomized omnipotence. Minimum mental resistance has us, uh…

ABORT ABORT WE’VE PIVOTED THE ARTICLE INTO BEING ABOUT AI AND SINNERS HASN’T EVEN BEEN MENTIONED YET

Sinners begins with a short-circuit. A short-circuit is when electricity travels along an unintended path— a non-useful path— a dangerous path. A short-circuit offers no resistance. A short-circuit immediately joins beginning and end. Sammie drives the car; he looks wounded, exhausted, empty-eyed; he returns to his church. He looks at his father. Time flattens, and we see someone else. There are sharp fangs and glowing eyes. His father warns him against sin. Sammie has seen terrible, terrible sins; the flashbacks are all very dramatic. They short out the story, but they are meant to introduce mental friction. What was that? When was that? Who are these people?

The most striking shorts are images of Remmick, the vampire antagonist. Vampires in Sinners are refreshingly archetypal. They burn up in the sun, and they hate garlic. They suck blood with messy, rending relish. They cannot cross thresholds uninvited. Remmick, however, is not an aristocrat; he does not seem predisposed towards looming seductively in ancient castles. He pulls from different archetypes, more a Petar than a Vlad. He is a displaced pagan Irishman. He preaches peace and love and an absolute togetherness. He is enamored with Sammie’s music because of its ability to reach through time; he thinks that it could take him home.

The least orthodox element of the vampires in Sinners is the continuity of their digested minds. When Remmick turns Joan and Bert, the Klan couple, he immediately comprehends Hogwood’s plan to kill everyone at the Juke Joint. After he turns Bo, he gains the ability to shock Grace via white boy threatens cunnilingus in perfect Taishanese. Joining Remmick’s coven kills you; it ends your isolated personhood, your discontinuity. (Obligatory Bataille sex-death lens upon the movie goes here; it isn't out yet for me to take proper screenshots, but imagine now in your mind Mary drooling into Stack's eager mouth.) You become one with him, and with everyone turned by him. Your whole mind becomes easy and frictionless; the differences just don’t matter anymore. Why worry? The Klan and a Black man perform an Irish jig, arm-in-arm.

My name is Remmick

This here's Joan and Bert

We believe in equality and music

We just came here to play, spend some money, have a good time

Can't we just, for one night, just one night

Just all be family?

The Klan couple also sing Pick Poor Robin Clean as twee-ly as possible. Compare this against this documentation of the original lyrics. As an aside, I was somewhat expecting Remmick’s consumption of culture to veer in the direction of Sorry to Bother You’s audience call-and-response scene, but the ugliness was not so abject.

One of my favorite character-demonstrating moments in the film is a split-second with Sammie. When Remmick insists that Sammie is the only one he really wants, Sammie is immediately willing to sacrifice himself for the group, and he takes a step forward. Everyone else, not at all willing to let that happen, pulls him back. Sammie is human. He eats out a married woman. He sins. But he is a good man; he shines a light.

His father, the pastor, is the tripped circuit breaker. He urges Sammie away from his music, from his passion and power, hoping to shepherd him back into a more complete separateness, a religious sequestering from the sinful world. And Sammie considers it, he really does. His hand quivers as he grips the shattered neck of his guitar.

But without a little resistance, nothing would ever get done.

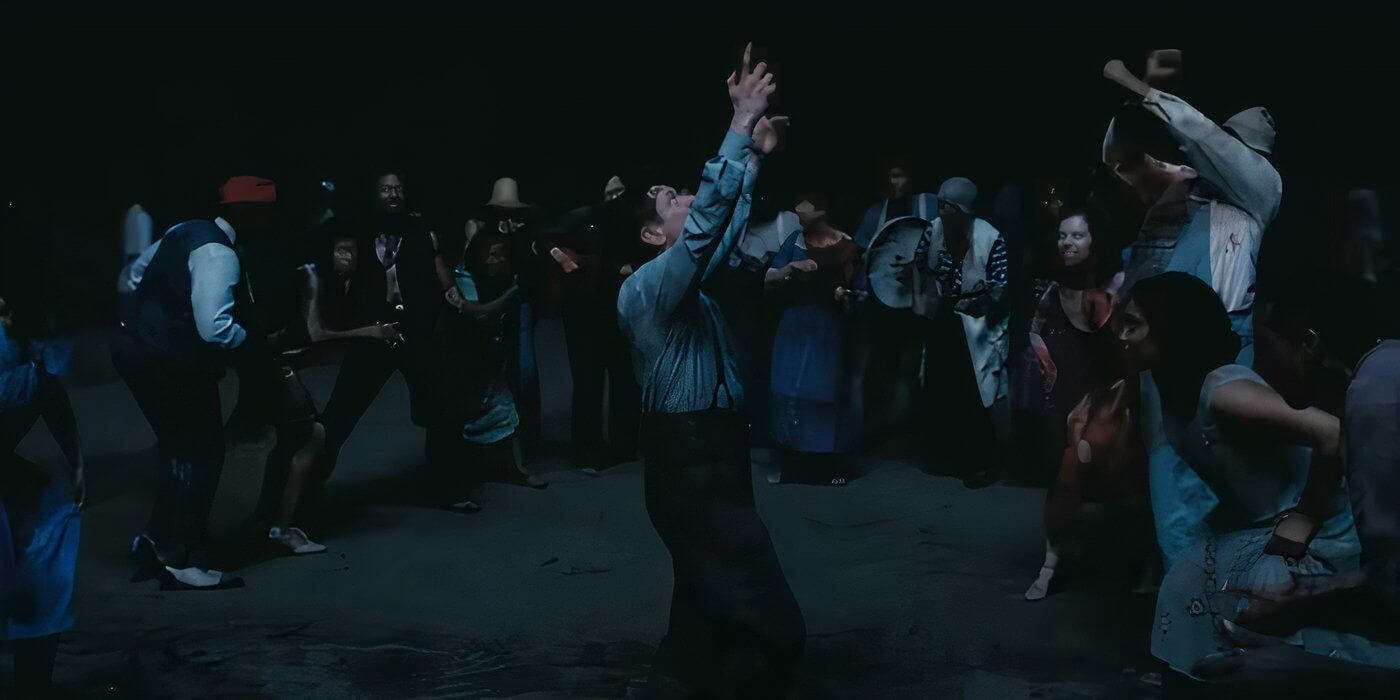

Sammie resists the frictionless appropriation-assimilation of the vampire until Remmick is cleansed by the rising of the sun; he presumably resists the appropriation-assimilation of the music industry for many years after that. As the movie dissolves into its credits, we see him visited by Stack and Mary after a show. Sammie is getting older, second by second; Stack and Mary are as they were when they died, eternal and perhaps stagnant. (They do update their outfits. But I like the fact that Sammie can connect to the past and the future, while Remmick, as a vampire, desired only the past.) Sammie asks if any day of their immortality— of their unending, frictionless love, freed of the racial pressures that had forced them apart in life— has been as good as that day at the Juke Joint, that day where Sammie invoked all of time from above via the divine transcendence of his music, as contrasted against the dead, soul-trapping homogenate of memory offered by Remmick’s vampirism.

No, Stack says. And then they leave.